Davide's Code and Architecture Notes - Tracking decision with Architecture Decision Records (ADRs)

When designing a system’s architecture, you have many choices to make. How can you track them? ADRs are formal documents to track the reasons behind your decisions, giving context and info about the consequences of each choice.

Picture this: you are the architect in charge of the design of the architecture. You make some choices; everything goes well for months. Then, all of a sudden, a new requirement arrives. That kind of requirement makes you think, “Is this architecture the right one? Should we change anything?”.

You don’t remember the reasons behind your choices. Why did you build your application that way? Why did you use gRPC instead of HTTP? Why Blazor instead of VueJS? If only you had something to remind you why you made some choices…

An Architecture Decision Record (ADR) is a way to describe, track, and discuss architectural and design decisions. It allows you to have a well-defined process to make informed decisions and to keep track of the whys behind your choices.

In this article, we will learn what ADRs are, their main parts, and how to generate documentation with open-source projects.

Structure of an ADR

An Architecture Decision Record (ADR) is a document that summarizes, tracks and explains critical architectural decisions. It’s not just the decision list: it’s a document that also tracks the current context, the alternatives considered, and the consequences of the final choice.

ADR is made of a set of files, each describing a decision. For each file you describe:

- The decision being made. For example, “Use Azure Service Bus as a queue platform”.

- The status of the decision. For example, “Under discussion”, “Accepted”, and “Superseded”.

- The time of this decision. For each ADR, you should specify when it was created and when it reached a new status.

- The context around the decision. For example, “We are currently using Azure as a main vendor”.

- The consequences of the decision. For example, “We accept to have vendor lock-in, but this way, we can more easily have support from the infrastructure team”.

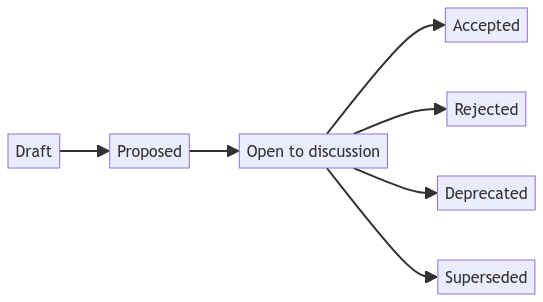

Usually, you should have a strict flow of status, ensuring that once it has reached one of the final statuses, the ADR decision cannot be changed. You can add more details, of course, but you should not change the decision taken.

Examples of statuses are:

- Draft: you are still describing the decision, and you are not ready to propose it yet.

- Proposed: you have explained all the details behind your decision so it can be officially discussed.

- Open to discussion: everybody can add comments to your decision, allowing you to consider other points of view and cover weak spots you did not find.

- Accepted: the team agrees with your decision, and you can now implement it.

- Rejected: the proposed solution is not feasible, so you cannot proceed with the implementation.

- Deprecated: the decision is no longer useful or necessary. For example, you removed the whole component from your system.

- Superseded: another ADR superseded the current one, making it obsolete.

Special mention to the superseded status: once a decision reaches the Accepted status, if you change your mind, you must create a new ADR to supersede the previous one. For example, say that ADR-30 was about “Use SOAP communication”. Then, you notice that you must change the communication protocol to gRPC. You can proceed in the following way:

- Create a new ADR, say ADR-105.

- Add a tag to ADR-105, something like supersedes ADR-30.

- Update the status of ADR-30 moving it to the superseded status, adding a reference to ADR-105.

This way, you can reconstruct the history behind a specific choice.

Best practices for creating ADRs

Let’s see some of the best practices for creating and maintaining ADRs:

- Use a consistent format and structure for each ADR. You can find several templates online.

- Store ADRs in a text file close to the code base relevant to that decision, or in a central repository if the decision affects multiple code bases. In this way, by putting the ADRs under source control, you can always review the history of the updates and keep everything tracked.

- Use a clear and descriptive file name, such as

ADR-001-use-azure-service-bus.mdor0001-use-azure-service-bus.md. - Keep ADRs concise and focused on one decision per document. Add only the necessary info to understand the rationale behind a decision.

- Update ADRs as the decision evolves or changes over time. Include the previous decision and why a change is made.

- Review ADRs periodically to ensure they are still relevant, accurate, and consistent with the current state of the architecture and the business needs.

If you want a nice list of ADR templates, have a look at this GitHub repository by Joel Parker Henderson.

A realistic example of ADR

Say that we have to pick a cloud provider for our serverless system. We need to choose between Azure and AWS.

Let’s see how an ADR describes why we chose Azure instead of AWS. Notice how the ADR describes the existing status, the reasons behind the decision, and also considers the possible drawbacks.

# ADR 001: Use Azure Functions instead of AWS Lambda

## Status

Accepted (2024-01-11)

## Context

We are developing a serverless system that needs to run various functions in response to events such as HTTP requests or message queue triggers. We need to choose a cloud provider that offers a reliable, scalable, and cost-effective platform for running these functions. The possible choices are AWS and Azure.

## Decision

We have decided to use **Azure Functions** as our serverless platform instead of AWS Lambda. The main reasons for this decision are:

- Azure Functions supports more programming languages than AWS Lambda, including C#, Java, JavaScript, Python, PowerShell, and TypeScript. This gives us more flexibility and choice in developing our functions since the team is currently working with several programming languages.

- Azure Functions has a better integration with other Azure services, such as Azure Storage, Azure Cosmos DB, Azure Event Hubs, and Azure Service Bus. This makes it easier to connect our functions to various data sources and destinations.

- Azure Functions has a lower cold start latency than AWS Lambda, which means that our functions will start faster when they are invoked for the first time or after a period of inactivity. This improves the user experience and reduces the response time of the system.

- Azure Functions has a more transparent and predictable pricing model than AWS Lambda, which charges based on the number of requests, the execution time, and the memory allocation of each function. Azure Functions charges based on the number of executions, the execution time, and the memory consumption of the whole function app, which is a logical grouping of functions. This makes it easier to estimate and control our costs.

## Consequences

By choosing Azure Functions over AWS Lambda, we expect to achieve the following benefits:

- We can use our preferred programming languages and tools to develop our functions.

- We can leverage the existing Azure ecosystem and services to enhance our system functionality and performance.

- We can reduce the latency and improve the responsiveness of our system.

- We can optimize our costs and avoid unexpected charges.

However, we also need to consider the following drawbacks and risks:

- We are locking ourselves into the Azure platform and creating a dependency on a single cloud provider. This may limit our options and increase our switching costs in the future.

- We need to learn how to use Azure Functions and its associated services and tools. This may require additional training and documentation for our team members.

- We need to monitor and troubleshoot our functions using the Azure portal or other third-party tools. This may introduce some complexity and overhead in our system operations.

There are several tools to generate ADR tools for your project.

- adr-tools by npryce: an CLI tool that automatically creates and manages the history of your ADRs. It’s a nice tool, but it hasn’t been updated in the last five years.

- adr-tools-python by tinkerer: available on BitBucket, relies on Python. It’s newer than the one by Npryce, but it hasn’t been updated since 2021.

- adr-cli by Jandev, which is a porting of adr-tools by npryce, but written in .NET

- ADR Manager, a UI tool that connects to your GitHub repository and generates ADR files.

Further readings

I first learned about ADRs thanks to Mark Richard’s YouTube channel. Here, Mark explains a lot of topics about Software Architecture, both from a technical standpoint and also tackling soft skills.

🔗 Developer to Architect, by Mark Richards

Here’s one of his videos:

This article first appeared on Code4IT 🐧

Another great source is Olaf Zimmermann’s blog, where he shares lots of great content about software architecture. He has a whole section focused on ADRs.

🔗 Olaf Zimmermann’s articles about ADRs

Wrapping up

In my opinion, ADRs are a great tool, especially for projects whose requirements are not defined upfront and that are expected to have a long lifespan.

One of the most important phases while taking architectural decisions is discussing the decision. An architect should not impose the architecture on the team. Other stakeholders, such as the developers, may have some concerns or notice a case that the solution cannot cover. It’s important to keep the ADR in the “Open to discussion” status and listen to every comment on this decision.

I hope you enjoyed this article! Let’s keep in touch on Twitter or LinkedIn! 🤜🤛

Happy coding!

🐧